Image

By Alvelyn Sanders-Swafford

August 12, 2021

Birmingham native Lisa Camel remembers when she and her friends would hop on their bikes and ride to the park just for fun when she was growing up in the late 1980s and early 1990s on the west side of Birmingham in the West End Manor neighborhood. Those memories of childhood fun and the feeling of safety motivated her to become a volunteer with Faith in Action Alabama, a multi-faith, grassroots organization with over 40-member congregations covering four areas of the state called hubs: Birmingham, Huntsville, Mobile, and Montgomery. In these hubs, volunteers meet monthly to strategize about creating policies that impact their respective community. Camel who now lives in McCalla, Ala. is a member of New Hope Baptist Church in Birmingham.

“I am a very passionate about the community where I grew up. When I was a little girl growing up, you could sit on the porch. Everybody knew each other. Everybody felt safe,” says Camel. She calls those the “good ol’ days,” when concerns about crime and violence were not at the forefront. Camel recognizes that one of the best ways to bring those days back is to get people in her hometown to the polls to vote. She believes when people vote, policies are impacted.

Lisa Camel as a child in Birmingham. Joyful, childhood memories led her to get involved with Faith in Action Alabama to help bring back the “good ol’ days.” Image courtesy of Lisa Camel.

Lisa Camel as a child in Birmingham. Joyful, childhood memories led her to get involved with Faith in Action Alabama to help bring back the “good ol’ days.” Image courtesy of Lisa Camel.Camel channels her passion for Birmingham as the leader of the Voter Engagement committee for the Birmingham Hub Leadership Council. “For me this change [has] to start somewhere and [that is] volunteering to join a team that’s working toward the goal of trying to make a difference,” says Camel. She’s been volunteering with Faith in Action Alabama since May 2017, and she served as the Birmingham-Jefferson County lead for the organization’s non-partisan Freedom Vote Campaign in fall 2020. Now she’s leading a new non-partisan voter engagement campaign for the upcoming municipal elections in Birmingham, which will be held on August 24, 2021, to elect the mayor, city council, and board of education.

Faith in Action Alabama hopes to reach 2,500 infrequent African American voters in Birmingham through phone banking and peer-to-peer contact with an app that allows text messages to be sent to the contact list in one’s phone. About fifty volunteers are on board so far working the phones and texting friends and family through August 23.

Volunteers can form teams by organizing members of their faith community or congregation, or persons can join a team already in place. The training teaches volunteers how to use the app and how to call voters (phone bank) from their own home. Phone bankers log into the VAN State Voices voter data system on their laptop. The system automatically supplies the target population and a script to follow. Camel shares that the Generation Z volunteers (those adults on the team who are 18-24 years old) may be more willing to use the peer-to-peer text app rather than call strangers on the phone. She concedes that the campaign is trying different avenues to reach infrequent voters in the African American community – and sometimes that infrequent voter might be among your own family or friends. This avenue is one route to engage young adult voters now and keep them as faithful voters for the long haul.

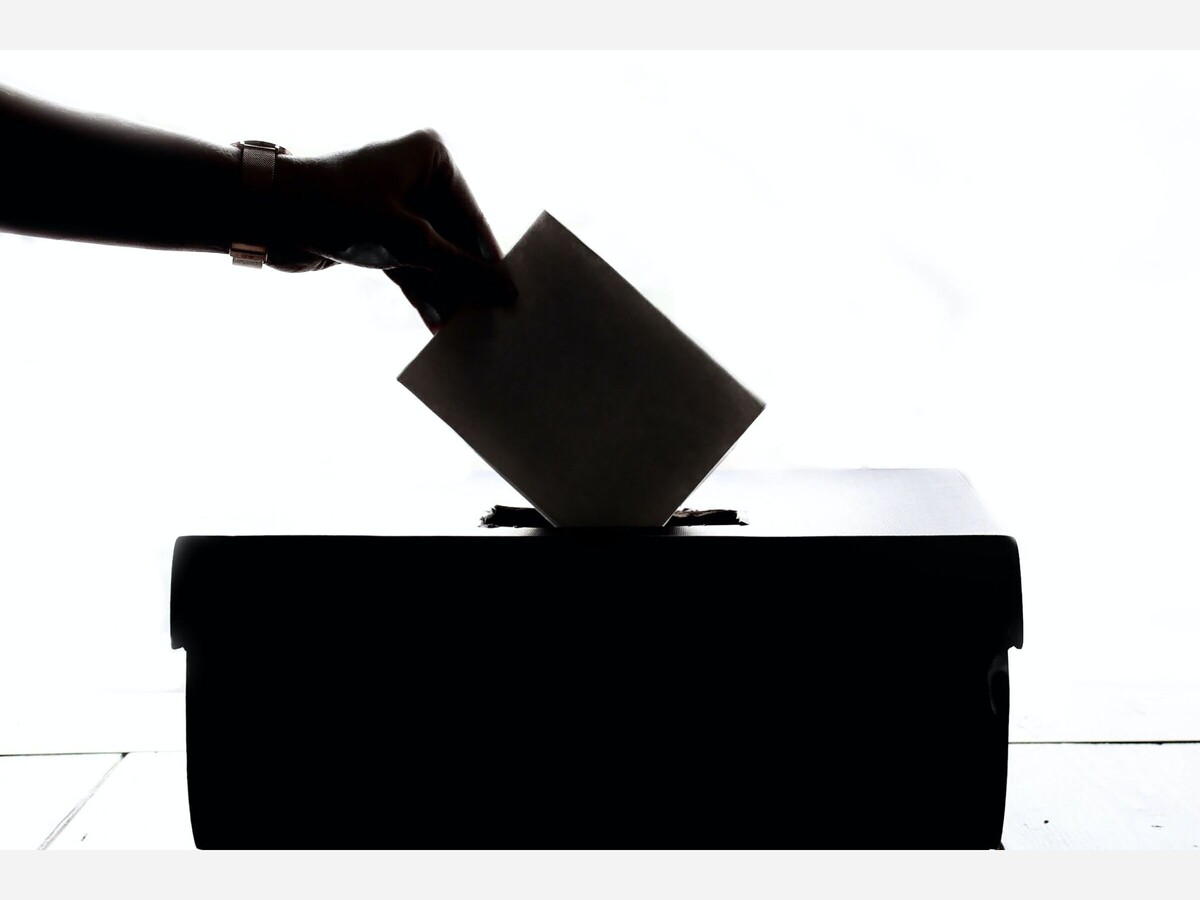

Gen Zers and millennials play a key role in the voter engagement and education programs at Greater Birmingham Ministries (GBM). Founded in 1969, GBM is a multi-faith organization that provides emergency services for those in need, and it works directly with low-income neighborhoods and people to respond to their needs through advocating for social justice and engaging the faith community as active agents of change. The organization’s 2021 Birmingham Election Guide was created by volunteers from GBM’s program called The Exchange, a group of Gen Zers and millennials who have been meeting monthly since April 2019 to discuss issues like transportation, environmental justice, reproductive justice, and voter suppression. The 2021 publication is the third guide the group has created since its inception.

Amanda Cherry, a millennial and a Community Organizer for Greater Birmingham Ministries, realized she and members of The Exchange were passionate about justice issues, but they needed a practical way to connect those issues to local politics – and to move the conversations from social media into action. “It occurred to me that one thing we could do was put together an election guide where we could take the issues that are important to us and highlight those issues in a guide related to the candidates,” says Cherry.

No one in The Exchange had ever created an election guide previously. Cherry admits they learned as they went along. The first guide was produced for the primary election in March 2020. GBM distributed 1,000 copies of that guide. The second guide was created to cover the 2020 General Election. The distribution leaped to 13,000 copies. Both guides included races on the ballot for voters in Jefferson County, including the presidential and statewide races.

The third guide presented a new challenge – finding information on local elections. The creators discovered that a simple internet search yields a bevy of information on presidential candidates, but more work is required for local candidates, the offices they are seeking, and the responsibilities of those offices. Cherry says they wanted to create a resource for voters in Birmingham by doing the “hard work.”

Additionally, the creators queried the community about what they wanted to ask the candidates. The topics that emerged are the ones included in the surveys distributed to those persons on the August 24 ballot. This year, GBM expects to distribute 20,000 copies of their third guide through a network of other social justice organizations, food pantries, and places of worship. Some will be mailed and given away at their own events like the Birmingham Elect Fest, which was held in Linn Park on August 7. The guide is available in Spanish as well.

The 2021 Birmingham Election Guide created by Greater Birmingham Ministries (GBM). Image courtesy of GBM.

The 2021 Birmingham Election Guide created by Greater Birmingham Ministries (GBM). Image courtesy of GBM.Birmingham resident Katelyn Foote, a member of The Exchange, who helped with researching local races and writing the Election Guide, believes it will help voters connect social issues to local policies. “The most basic way we can start working to address them is by being informed voters,” says Foote.

But there are always issues in every race in every city in every state. Everyone is concerned about safety, right?

Yet, organizations like Faith in Action Alabama and Greater Birmingham Ministries can’t ignore the fierce urgency of now when it comes to voter suppression without calling into question their mission and efforts to engage voters. Voter suppression is the elephant in the room.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice report, “Voting Laws Roundup: July 2021” published on its website July 22, 2021, at least 18 states passed 30 laws restricting voting access between January 1 and July 14 of this year. Alabama was one of those states. The report goes on to share that in 49 states, over 400 voter-restriction bills have been introduced in state legislatures during the 2021 session. “This wave of restrictions on voting — the most aggressive we have seen in more than a decade of tracking state voting laws — is in large part motivated by false and often racist allegations about voter fraud,” the report declares.

Faith in Action Alabama states the following as a part of its mission, “Our mission is to honor God by dismantling systemic racism to create pathways of opportunity for all Alabamians.” In response to this writer’s email inquiry about how voter engagement helps Faith in Action Alabama meet that mission, Daniel Schwartz, Executive Director, replied, “Increasing the voting power of the African American community is critical to dismantling systemic racism. There has been limited effort, i.e., resources invested, to engage infrequent African American voters, which has undermined the public voice of Alabama's African American community. Expanding Alabama's African American voter turnout is a pathway to helping wage a campaign to dismantle systemic racism in Alabama.”

Critics of the recent voting-restrictive bills argue that distinctive public voice is being silenced swiftly.

Indeed, it was the public voice of African Americans that served as the catalyst for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. That voice rose from sanctuaries of Black churches in the deep south, and it rose from one particular Alabama bridge splattered with blood.

In 1965, the late Rev. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, who was with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had been meeting regularly with the people of Selma, Alabama and the Dallas County Voters League, including longtime voting rights activist, the late Amelia Boynton. The meetings were held at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church to plan a march from Selma to Montgomery to highlight the lack of voting rights for African Americans in the south. After the Sunday morning worship service at Brown Chapel on March 7, 1965, about 600 marchers, led by Williams, Abernathy, and Lewis, set out to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge just a short walk from the church. When they crossed the Alabama River, they were met at the other side of the bridge by mounted state troopers who had been deputized by Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark. After the marchers peacefully stood their ground, the troopers charged the marchers, beating them with billy clubs and spraying them with tear gas. No one in their reach was spared from serious injury, including Boynton, one of the many women on the bridge. Even children, like 9-year-old Sheyann Webb-Christburg, had to run for safety back to Brown Chapel AME Church.

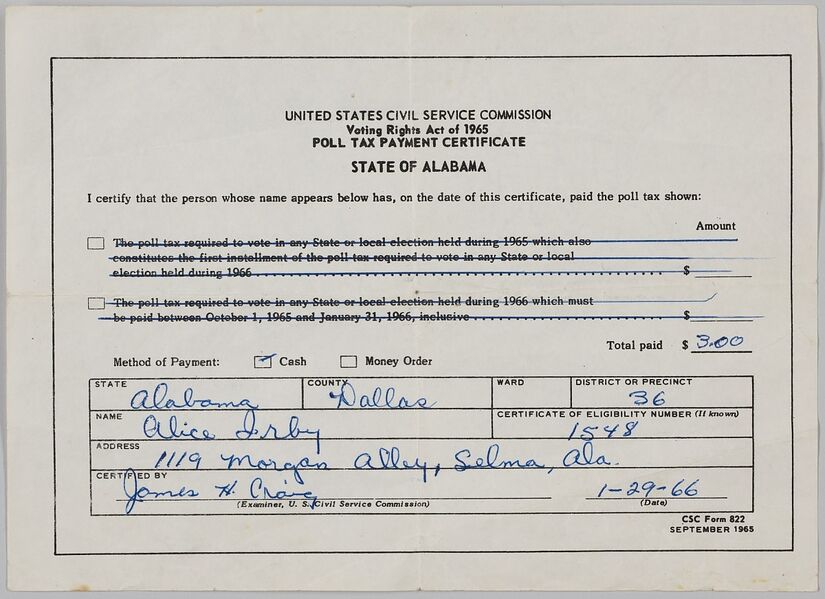

That day became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The news coverage of the beaten, bloodied marchers on the bridge traveled globally. Suddenly, decades of civil rights activism, bus rides, bombings, lynchings, unsolved murders, poll taxes, jelly beans in jars, and peaceful marches finally seized the attention of the nation when the scene from Selma flickered for the world to see.

Bloody Sunday prompted President Lyndon B. Johnson to give a joint speech before Congress on March 15, 1965. In the speech, titled “The American Promise,” Johnson presented his case for passing the Voting Rights Act, “For the cries of pain and the hymns and protests of oppressed people have summoned into convocation all the majesty of this great Government--the Government of the greatest Nation on earth. Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country: to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man. . . . But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

The eventual march from Selma to Montgomery was led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on March 21, 1965. By the time the marchers reached the capitol in Montgomery, 25,000 people had joined the march. On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

The Act gave the promise of democracy a chance to thrive for all Americans. But it was cut from its life source in 2013 by the Supreme Court ruling in Shelby County v. Holder. In that decision, a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one requiring jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to get permission from the Department of Justice or a federal district court in Washington, DC before making any changes to its voting procedures, was struck down.

One Alabama city giveth (Selma); one Alabama county (Shelby) taketh away.

The Brennan Center for Justice report on recent voting laws goes on to say, “Congress has the power to stem the tide. The For the People Act, passed by the House and now awaiting action in the Senate, would mitigate the effect of many state-level restrictions. And the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would protect voters by preventing new discriminatory laws from being implemented.” However, on August 11, the U.S. Senate adjourned for a monthlong recess without advancing any voting rights legislation.

A poll tax certificate issued to Alice Irby of Selma, Alabama by the United States Civil Service Commission, Voting Rights Act of 1965. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from the Family of Alice Irby - January 29, 1966.

A poll tax certificate issued to Alice Irby of Selma, Alabama by the United States Civil Service Commission, Voting Rights Act of 1965. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from the Family of Alice Irby - January 29, 1966.In the meantime, voting rights activists, community organizers, political action groups, pastors, clergy, church folk, congregations, faith-based organizations, barbers, hair stylists, mothers, fathers, aunts, and uncles will remain on the frontlines doing what they can to maintain the right to vote for people who have been disenfranchised historically – and presently.

“It does not take a rocket scientist to know that we are in crucial times of social upheaval and stress. Several states already are attempting to roll back the significant gains of the past of the civil rights era – the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Those protections are being stripped on the state level and I think now more than ever is a time for faith-based groups and churches to really be aggressive,” says Rev. Dr. Tyshawn Gardner, an adjunct professor at Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham and in the Department of Gender and Race at the University of Alabama.

So yes, considering the history of Black churches across the south in advocating for human and civil rights, the faith community would be involved in engaging and educating voters. After all, the organizers of the Selma to Montgomery March were able to meet in Brown Chapel AME Church because the pastor, Rev. P.H. Lewis, with the approval of Presiding AME Bishop Isaiah H. Bonner, defied the Gov. George Wallace’s ban on mass meetings by opening the doors of the church.

While Faith in Action Alabama and Greater Birmingham Ministries are multi-faith, multi-racial organizations, Gardner contends that the work they are doing is a continuation of the work of the tradition and the values of the Black church from the 1960s. “I think that in the United States, the Black church sets the model. We know that during Reconstruction – and before that during slavery – and during the civil rights movement, African American Christians have led the quest for freedom in the United States for communities that have been disenfranchised. We have not closed the door to other faith groups who have wanted to participate in those liberative activities,” says Gardner.

For Lisa Camel and Katelyn Foote, they found a group of people doing the work they wanted and needed to see being done. They found their tribe in a faith-based organization. While the two women have never met and were interviewed separately for this article, they share similar missions and speak the same language. Camel is passionate about the Birmingham she once knew as a child. Foote is passionate about the Birmingham she’s getting to know again after moving back to the city where she attended college (Samford University). Both women are working in-between what was and what could be. Yet, it is their faith that brings them to the table to do the work important to them – engage and educate voters.

Maggie Davies (left) and Katelyn Foote (right) distribute copies of the Birmingham Election Guide. They are members of The Exchange, a volunteer group of mostly Gen Zers and millennials who created the guide for Greater Birmingham Ministries. Image courtesy of GBM.

Maggie Davies (left) and Katelyn Foote (right) distribute copies of the Birmingham Election Guide. They are members of The Exchange, a volunteer group of mostly Gen Zers and millennials who created the guide for Greater Birmingham Ministries. Image courtesy of GBM.“I do have a strong faith background. I do still identify with the Christian faith. But I do really like being involved with an organization that is faith based but that recognizes multiple faiths in a place where people come together and work together on things. That does really draw me in. One of the things that has been really important to me is faith in action,” says Foote. Camel agrees, “If we want to change policy, it’s one thing to talk about it, but we have to put faith in action.”

For Camel, that action must be sustained. It is about the long game. When she speaks of her work with Faith in Action Alabama and reaching infrequent African American voters, Camel says she stresses the importance of registering people to vote continuously not just during election cycles, encouraging voters to update their registration when they move, and informing voters of the constant changes in voting locations and the ever-changing rules on voting absentee.

As the Vice President of Student Affairs at Stillman College and as the pastor of Plum Grove Baptist Church both in Tuscaloosa, Rev. Dr. Tyshawn Gardner sees first-hand the challenges African Americans face in lifting their voice at the polls. “Let’s be honest,” says Gardner, “in communities of color it is really tough to sometimes navigate the complex process of casting a vote.”

But Camel is not giving up, “We need every vote. Every vote matters. And every vote makes a difference. If you want to make a difference, if you want change, it starts with where the power is. The power is in the vote.”

For more information about how to exercise your power to vote or empower others to vote in the upcoming Birmingham municipal elections, contact:

Greater Birmingham Ministries

The Birmingham Election Guide is available online.

(205) 326-6821

and

Faith in Action Alabama

https://www.faithinactionalabama.org/

(205) 451-3352

Have an idea for a story? Want to share news from your faith community? Contact me through the Faith Works – Birmingham site. Click the yellow SHARE YOUR NEWS button. I look forward to hearing from you. Thank you for your support.

About the writer:

Reverend Alvelyn Sanders-Swafford is the founder and editor of Faith Works – Birmingham, a news site powered by Patch Labs. She is an award-winning journalist and filmmaker. She serves as the pastor of St. James African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church-Avondale in Birmingham, Alabama, her assignment as an Itinerant Elder in the AME Church. Sanders-Swafford is the author of the book, “Lord, Have Mercy: 5 Go-To Prayers When You Need To Pray, But Don’t Know What To Say” (See alvelyn.com.). For many years, she served as a contributing reporter for Atlanta’s NPR (National Public Radio) station, WABE 90.1FM. Her work has appeared in Essence magazine and the Atlanta Journal Constitution newspaper among other publications.